I know I haven’t posted any real sewing/tailoring content from Sartoria Insulindica for something like one and a half years by now, so I guess here I am, playing catch-up with the actual amount of patternmaking, fitting, sewing, and all the associated kind of activities I’ve been involved in over that timeframe. One of the most significant projects I’ve been working on since the last update is yet another attempt at developing a HEMA (historical European martial arts) jacket model that would be suitable for scaling up into larger-scale production. Meet Bess.

Why Bess? Well, the previous model was Nellie, and it happened to be the third model in the series (after the 2017 experimental gambeson and the Gorillambeson). The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Mitsubishi G3M bomber back in World War II was given the Allied codename “Nell.” The G4M was “Betty.” So why not run with the theme and name this one “Beth” or “Bess?”

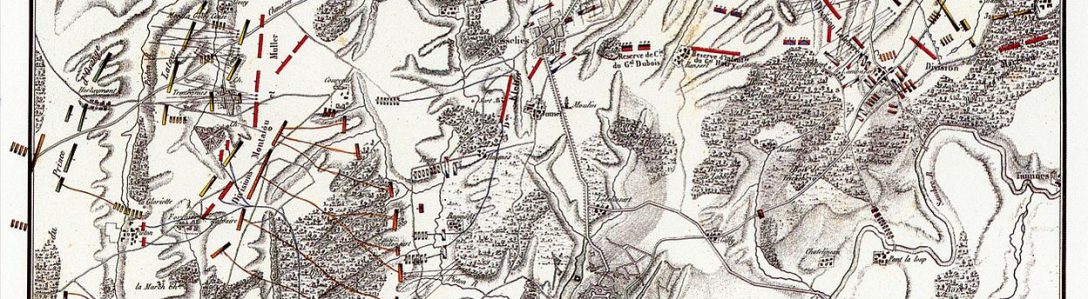

It took me less than two months back in 2022 to come up with a satisfactory pattern for the body pieces, which has required nothing more than minor tweaks since then. The sleeves were a different matter entirely. I spent the better part of this year drafting, fitting, redrafting, and tweaking things until I felt like I had a couple of options that worked decently enough by September. The first was a multi-part sleeve as in the picture below, with the lower arm being encased in a separate segment that included an elbow hinge:

The second variation (again, picture below) was actually a simplification of the first one into a conventional two-piece curved sleeve pattern.

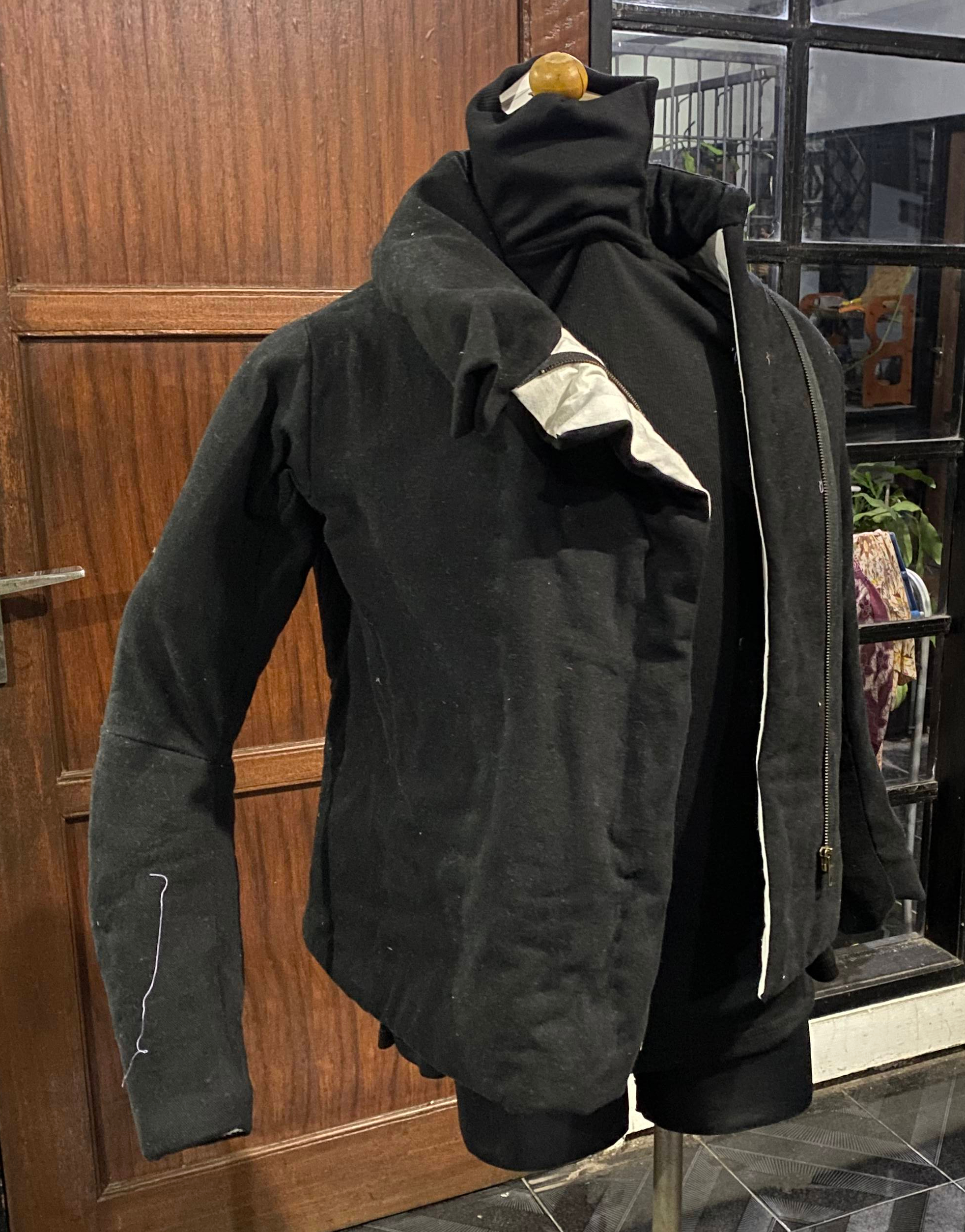

Some of you may remember that I used a similar elbow hinge for my personal jacket project several years ago, so let’s bring a picture of that back up as a reminder.

But there were several differences between that jacket and Bess, which led to substantially different results. To understand the reasons, let’s go back to the article where Tasha Kelly coined the term “elbow hinge” for a feature found in the sleeves of Charles de Blois’ pourpoint. There, the elbow hinge was obviously intended to provide freedom of movement in a very close-fitting sleeve; while my personal jacket’s sleeve wasn’t quite that tight, it came out pretty snug once the padding materials had been inserted. This wasn’t a problem since I was always able to check and tweak the fit on my own arms at every step of the process. But Bess is intended as a ready-to-wear garment. It has to fit a variety of bodies (or rather arms). So the basic sleeve pattern has to start out being on the loose side, and . . . well, there goes the rationale for cutting the sleeve with an elbow hinge to begin with.

Even with this knowledge that the elbow hinge would probably be redundant at best, I decided to try out both the simple and the multi-part sleeve patterns on Bess anyway. The results only confirmed my skepticism. The elbow hinge on a loosely-fitted sleeve didn’t offer any significant advantages in mobility over the simple curved sleeve, and in fact I found some reason to worry that it might actually offer less mobility in some scenarios. The thing is, I used slightly modified numbers from the Indonesian national standardisation body’s table of clothing sizes, and the standard size that fits me in width/circumference is generally too long in the vertical dimension. So the standard sleeve length is also too long for me and the pocket that’s supposed to accommodate my elbow in the lower sleeve ended up being slightly too low along the arm. I could just barely make it work by tugging the lower sleeve up to sit in the correct position, but that bunched up the padding inside the upper sleeve and made it a little harder to move the right arm into certain positions. Ouch.

Now, that effect isn’t going to be a problem for everyone, so I don’t think the continued use of elbow-hinge designs in the most popular HEMA jacket models as of late 2023 (such as the SPES AP Light and FG) is particularly detrimental to the wearers’ mobility in any significant way. After all, most of these makers have some kind of customisation options available, and this customisation would usually include adjusting the lengths of the upper and lower sleeve segments so that the elbow hinge could actually offer some improvement to the wearer’s range of motion. But when it comes to jackets bought right off the catalogue in standard sizes, this advantage isn’t going to be present to the same degree, especially since the sleeve is probably going to be cut loosely enough that there’d be enough mobility with or without the elbow hinge. In this respect I can’t help thinking that the elbow hinge in these non-customised jackets is more of a style line added for aesthetic/visual interest rather than any tangible mechanical benefits. It’s pretty, it probably won’t impede range of motion, people have come to expect it, and it’s not that much more work to add a short seam there with a sufficiently powerful sewing machine. So why not?

That being said, if you’re a maker thinking of developing your own jacket for the armed disciplines of HEMA or related activities, all of this means you can rest easy knowing that the elbow hinge isn’t going to be strictly necessary for your sleeve design — unless you want it to be both close-fitting and substantially padded. If you’re fine with a looser fit to your sleeve — especially if your goal is to make or develop a budget model — then a simple two-piece curved sleeve is probably going to be easier to cut, fit, and construct.

So there. I hope these ramblings are going to be of some use to at least some readers. There’s also the bigger issue of cutting the armscye and the sleeve to allow the wearer to raise and move their arms without shifting the body of the jacket too much, but like I said, it’s a bigger issue that tends to get oversimplified in online discourse and it’ll take more time for me to write about it.